A Tale of Two Cameras — Unraveling the Mystery of the First Hasselblad in Space.

(Photo Credit, NASA / Andy Saunders - Gemini & Mercury Remastered)

Disclaimer: The following is my opinion based on the information I have available.

The cameras we took with us when we first left Earth in the 1960’s are a fascinating series of artifacts that captured some of the most iconic images ever taken — moments that shaped how humanity first saw its home from afar.

In 2014, one of those relics from the dawn of the space age resurfaced at auction. Listed as “The First Hasselblad In Space,” it was the genesis camera — the blueprint for all cameras that flew to the surface of the moon, and the beginning of Hasselblad’s storied connection with NASA that lasted through the shuttle-era. The excitement within the collector community was undeniably palpable. Multiple publications picked up the story, and it ultimately sold for a cool $275,625 USD to a private collector.

I’ve come to know this camera intimately, having spent countless hours scrutinizing every photo and related document to reverse engineer how it was modified. I even built a workshop in my garage to make a series of hyper-accurate replicas to help finance my admitted obsession with the thing, noting every scratch, every detail, down to what typewriter model was used to create the labels.

Then, seven years later, a gut-wrenching twist: a second Mercury-era Hasselblad appeared, and it also claimed to be the first.

A rapid series of questions ran through my head, along with a few expletives that I won’t repeat here. Two “first” cameras? How does that happen? Was this new camera legit… if so, which camera is which? I needed to know.

But where do you even start? Information about many of the Mercury cameras is already scarce. Each comes with its own series of little mysteries — when it was modified, when (or if) it flew, and where it ended up. Beyond a few books and sparse placards in museums, much of what’s known about them is anecdotal at best, and in danger of being lost to time, fading with the brilliant generation that made them possible. That, or forgotten in archives not yet made available to the internet.

With what is available, it’s hard to discern what’s accurate. There have been many cases where the NASA documentation itself is completely wrong, including how an Apollo 17 camera listed as “OFFLOADED” on the moon recently turned up in Switzerland. All this to say, it takes a fair bit of research to find yourself on steady footing with truth.

As with any passion, when you’re in this deep, there’s joy in uncovering even the smallest of details. When pieced together, they help paint a more complete picture, and on the rarest of occasion, can contribute back to the collective knowledge surrounding such historical objects.

The story that follows, however, is certainly not joyful, and honestly one that I’ve hesitated to tell for a few years because of the implications it may have for the rather wonderful people close to the matter… especially with the kind of money involved. But I believe what I’ve found should be shared, or at least the conversation had, to prevent any confusion in the future.

1962 - How the Hasselblad Entered Space

Let’s set the stage. In the early summer of 1962, at the height of the space race, astronaut Wally Schirra was slated to become the ninth human to fly to space aboard Mercury Atlas 8 (MA-8).

As one of the infamous Mercury 7 astronauts, Schirra had watched four of his peers fly before him on short duration missions that mostly focused on proving that we could, indeed, get up there and survive. His flight would push the boundaries. Aiming for seven orbits, it was to be the longest yet, focused mainly on the engineering challenges facing a spacecraft in extended orbit.

Wanting to bring a better camera than the consumer-grade cameras that flew before, Schirra polled his circle of press photographer friends — the same ones from National Geographic and Life Magazine assigned to follow the astronauts and their families around.

Their recommendation? Bring a Hasselblad. A 70mm medium-format camera, it was twice the resolution of the 35mm Ansco Autoset that John Glenn had picked up at a corner store after a haircut. Better yet, it had interchangeable film magazines, which made it easy to swap film mid-roll if he needed — a convenience that would prove useful under the tight constraints of a space mission while wearing a full pressure suit.

The problem was… it was rather bulky, and at the time, photography was not seen a high priority task. NASA leadership, especially Flight Director Chris Kraft, blamed Scott Carpenter, who flew on MA-7, for spending too much time enjoying the view and wasting precious fuel to maneuver the spacecraft for photos, which allegedly caused him to miss his targeted splashdown point by 250 miles. This wasn’t really the case, but no matter actual cause, Kraft’s mind was made up, so it took some real pushback, even a tearful plea from Schirra, for them to begrudgingly relent. The camera was eventually green-lit, and Hasselblad was purchased for his mission.

The job of modifying the camera fell to Roland “Red” Williams, an RCA engineer contracted by NASA to prepare photo equipment for use in space. The most obvious goal was to remove as much weight as possible, given the every gram counted with these early rockets. Everything unnecessary had to be removed, from the leatherette to the heavy glass mirror. Lightening holes were drilled to remove excess material even the unseen recesses of the lens.

The other goal was to make it easy to aim the camera at an intended target without the use of the waste-level finder. A small cold shoe, found in the pile of parts removed from the previous flight’s camera, was affixed to one side to hold a custom ring sight fashioned from a surplus WWII artillery gun. It was a rush job, but it was enough to get the camera flight certified, and a few last minute photographic weather experiments added to the flight plan.

Roland “Red” Williams (right) walks Wally Schirra (center) though his flight ready camera.

On September 20th, thirteen days before his flight, Schirra had his final camera familiarization, with Mr. Williams walking him through the modifications. A staff photographer captured the moment, which shows the astronaut aiming the camera as he would in space, with a second, unmodified Hasselblad sitting in front of him on the table. The equipment was then transferred to Hangar S, Mercury’s headquarters at the cape, photographed as part of MA-8’s preflight kit, and launched in spectacular fashion at 7:15 AM eastern time on October the 3rd, 1962.

Ultimately, higher resolution photos from MA-8 proved so useful, a Hasselblad was used again by astronaut Gordon Cooper on MA-9, which lasted a whopping 22 orbits. Fifty-two years later, it’s Cooper’s camera that reappears at auction, but was it also Schirra’s?

2014 - The Auction Camera

RRAuction lists “The First Hasselblad in Space” for sale in 2014

According to the listing, the camera for sale was flown on both MA-8 & MA-9, making it the first Hasselblad in space.

The MA-9 provenance is pretty clear. Cooper is seen posing for a photo in his twilight years, aiming the device as he did decades earlier. A letter from the astronaut describes it as the one he used on MA-9, identifying the writing on the film magazine as pertaining to his flight.

Gordon Cooper with his MA-9 Camera

Writing on the a film magazine pertaining to the MA-9 mission

Signed MA-9 Letter by Gordon Cooper

The case for MA-8 is much thinner. The auction researchers compared scratches on the camera body and the serial number of the lens with a photo erroneously identified as a post-flight photo from MA-8. The photo was actually taken in 1963 after MA-9 had flown, and shows both the MA-8 film magazine, and the flown MA-9 Magazine with white writing. Technically it is after MA-8 flew, but so much could have changed if it was also used on MA-9.

The 1963 Project Mercury Summary Report, which contains the photo, was published after all flights had concluded and describes the camera and its separate components: “The 70mm Hasselblad camera shown in the figure was used for both missions.” In hindsight, the documentation isn't clear if it was the same camera that was flown on both missions, or the same type of camera. The difference here is pretty important, and it can be read both ways.

Another document cited by the auction house has the same ambiguity. It lists the onboard equipment for MA-9, stating the qualification for Cooper’s camera as “Flown on MA-8.” It also qualifies a 35mm Robot Recorder body as having been flown on MA-7. A quick search shows the Robot cameras are two distinctly modified cameras that can be readily found in the Smithsonian collection. The MA-9 Robot Recorder was the same type of camera, but not the same camera.

This is the only evidence offered that ties the camera to MA-8. For years, I didn’t question it. As it would turn out, a chance post on Twitter would help shed some light.

Auction description of the camera comparing it to the 1963 Project Mercury Summary Report image

Project Mercury Summary Report image from 1963, originally captioned “The 70mm Hasselblad camera shown in the figure was used for both missions”

RR Auction reference that identifies the MA-9 camera as the same type flown on MA-8.

2021 - Steve’s Camera

Col. Chris Hadfield holds the first Hasselblad in space.

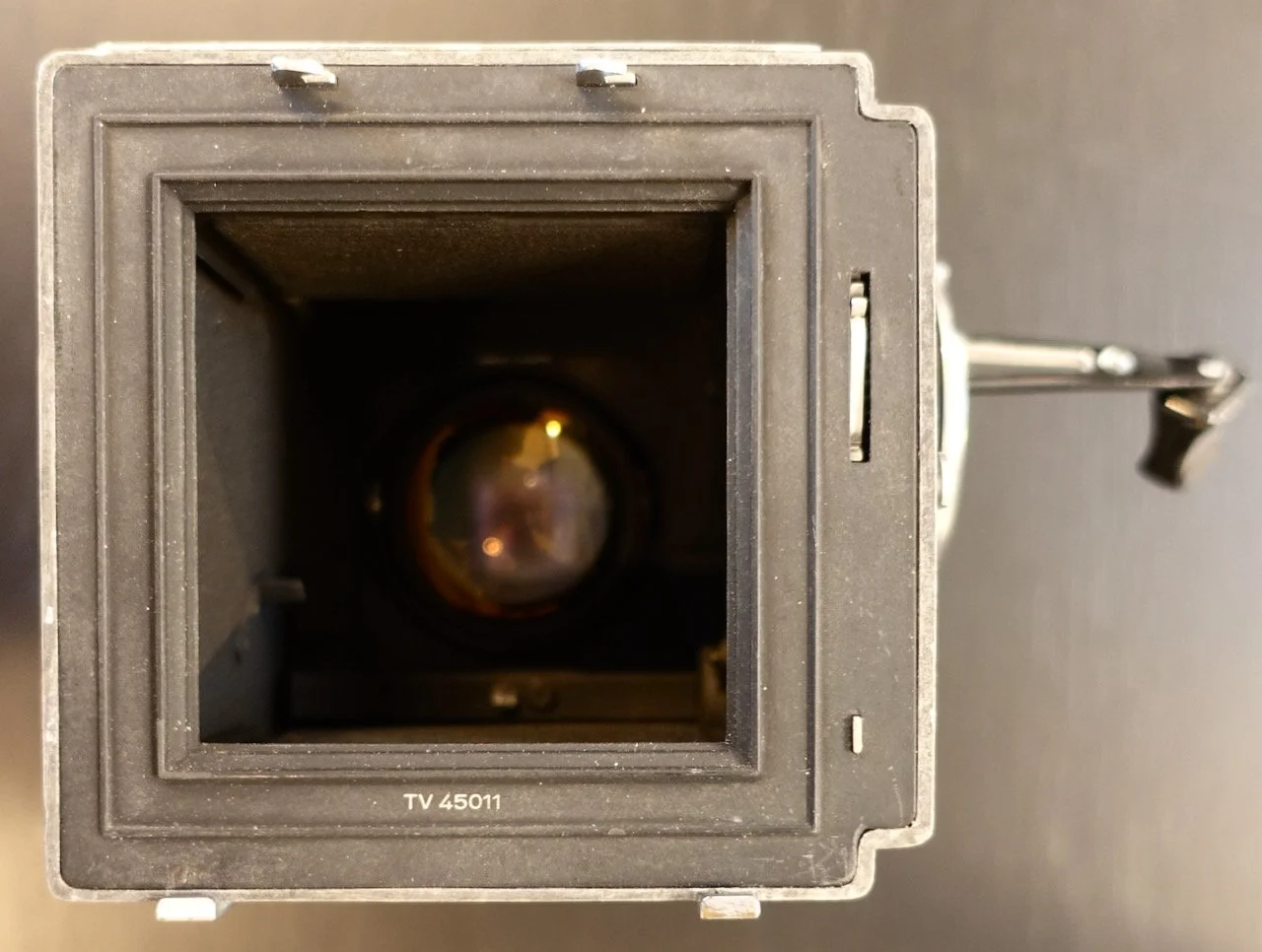

In October 2021, I happened upon a tweet by renowned investor and space collector Steve Jurvetson, seen smiling next to Astronaut Chris Hadfield. In Col. Hadfield’s hands is a camera that looks remarkably like the one that sold. The caption identified it as “the first Hasselblad in space.” Ok, maybe he was the owner who bought it at auction? I immediately reached out to Steve, and he kindly provided detailed photos over a series of emails for me to further examine what he had.

MA-8 Hasselblad, as owned by Steve Jurvetson. Photo Credit: Mike Smithwick

The first thing that stood out was the lens had a different serial number. Weird. Then I noticed the aluminum panel of that covers what used to be the viewfinder was slightly undersized, and seemingly more haphazard in how it was drilled than the camera that I knew.

It became immediately clear it wasn’t the same camera.

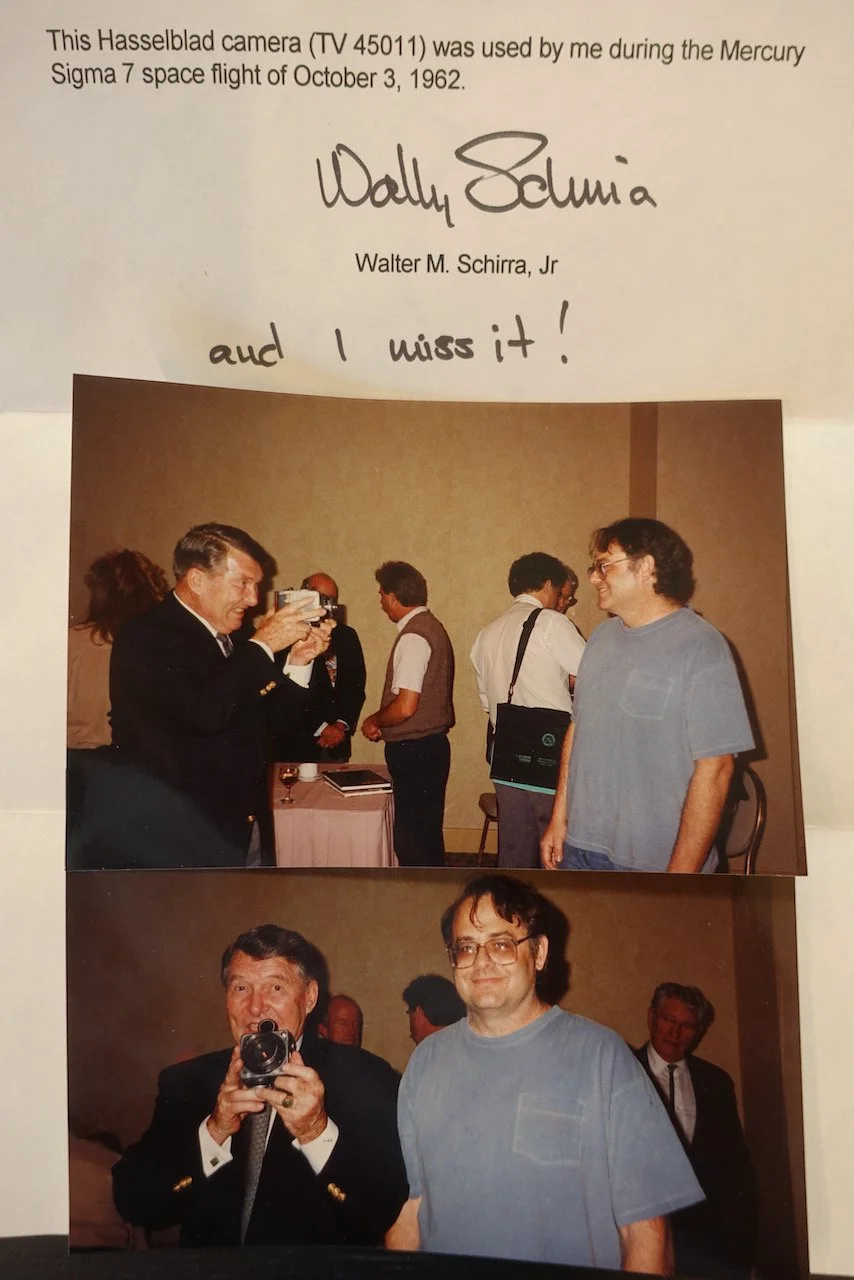

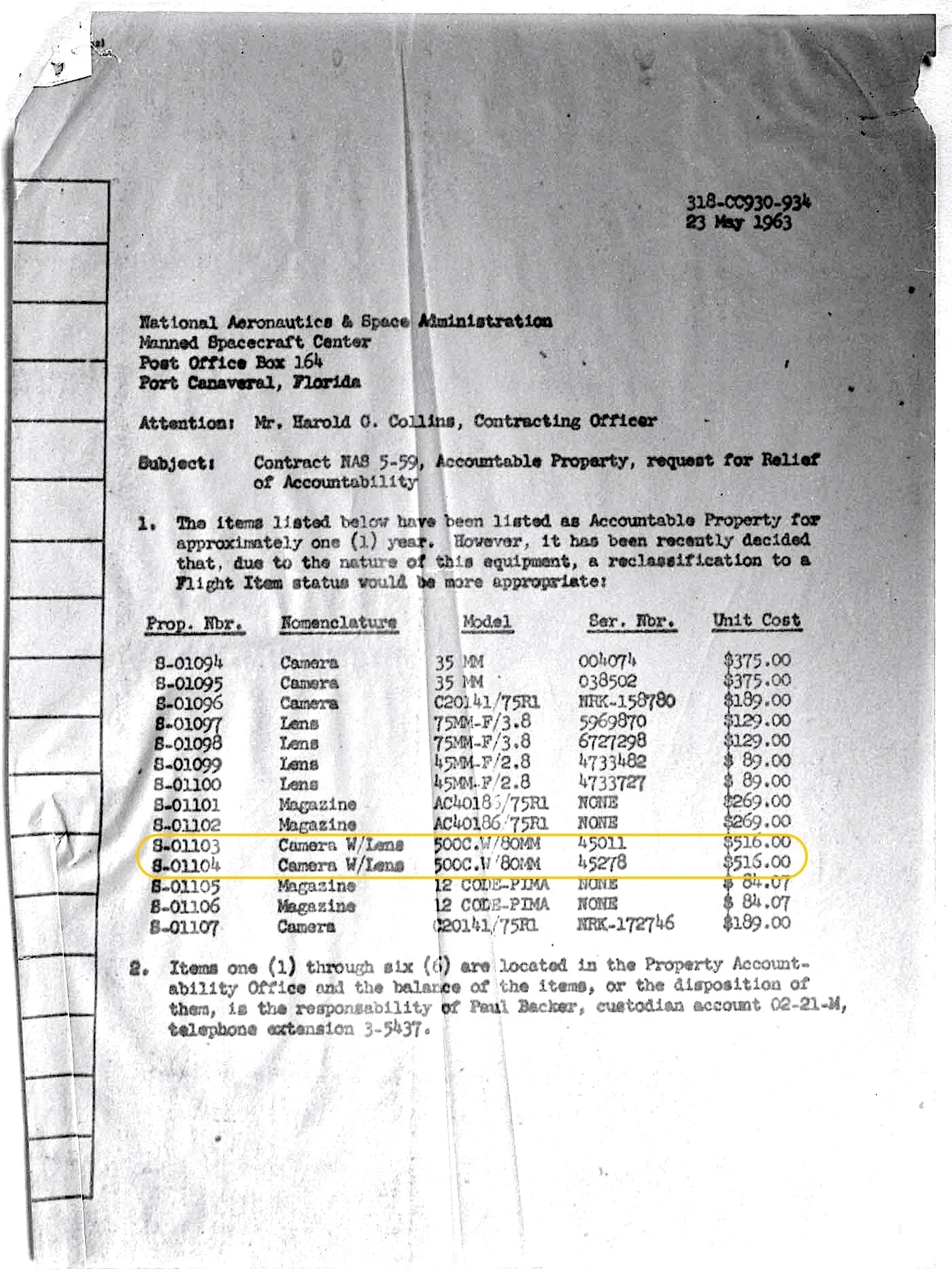

Jurvetson also presented two crucial documents: a signed letter from Schirra himself attesting to the camera, identified by its serial number, as being flown on MA-8, and a NASA / McDonell inventory dated days after the completion of Cooper’s flight that list two Hasselblads as being purchased for the program.

Astronaut Wally Schirra holding his camera after its previous sale.

McDonnell Inventory showing all cameras used on Project Mercury, including two Hasselblads by serial number.

Two Mercury Hasselblads!? My mind was blown. This was the missing clue that proved there were indeed two in the mix. Thinking back, Cooper claimed his camera was used on MA-9, but he didn’t specify if he had re-used good o’l Wally’s camera. But let’s put aside the signed astronaut testimony for a moment. Is there irrefutable evidence not based on witness accounts that can shed some light on the bigger picture?

The Pre-flight Photos

I decided to approach the question by comparing each of the cameras to preflight photos of the equipment used on MA-8 and MA-9. I knew NASA procedure was to document equipment before and after each flight — I had come across low-res scans of these kind of images in early Mercury documentation. Maybe, if I could somehow track down high resolution versions of these images, I could make a more accurate comparison of the cameras to determine which camera was which.

So, where do we find these high-res versions?

MA-8 Preflight Photo (LOC-62-7465)

Incredibly, I was able to track down a rare print of the MA-8 preflight photo listed for sale online by collector. The print had unfortunately already sold, but I emailed the seller anyway, and a kind fellow by the name of Jerome responded, graciously sharing a high resolution scan, along with the context of how he came across it. His family lived in Cocoa Beach, Florida from 1958 to 1985, space-coast central, where the Mercury astronauts lived and infamously partied. Jerome’s father was an aerospace journalist, and a member of the Office of Public Affairs VIP mailing list. Over the years, they had amassed a large collection of press photos directly from NASA, including this one from MA-8.

Titled "MA-8 Walter’s Camera Ditty Bag Contents,” the image is remarkably sharp, showing the camera to be used by Wally, along with other items in his ditty bag that match the MA-8 mission profile.

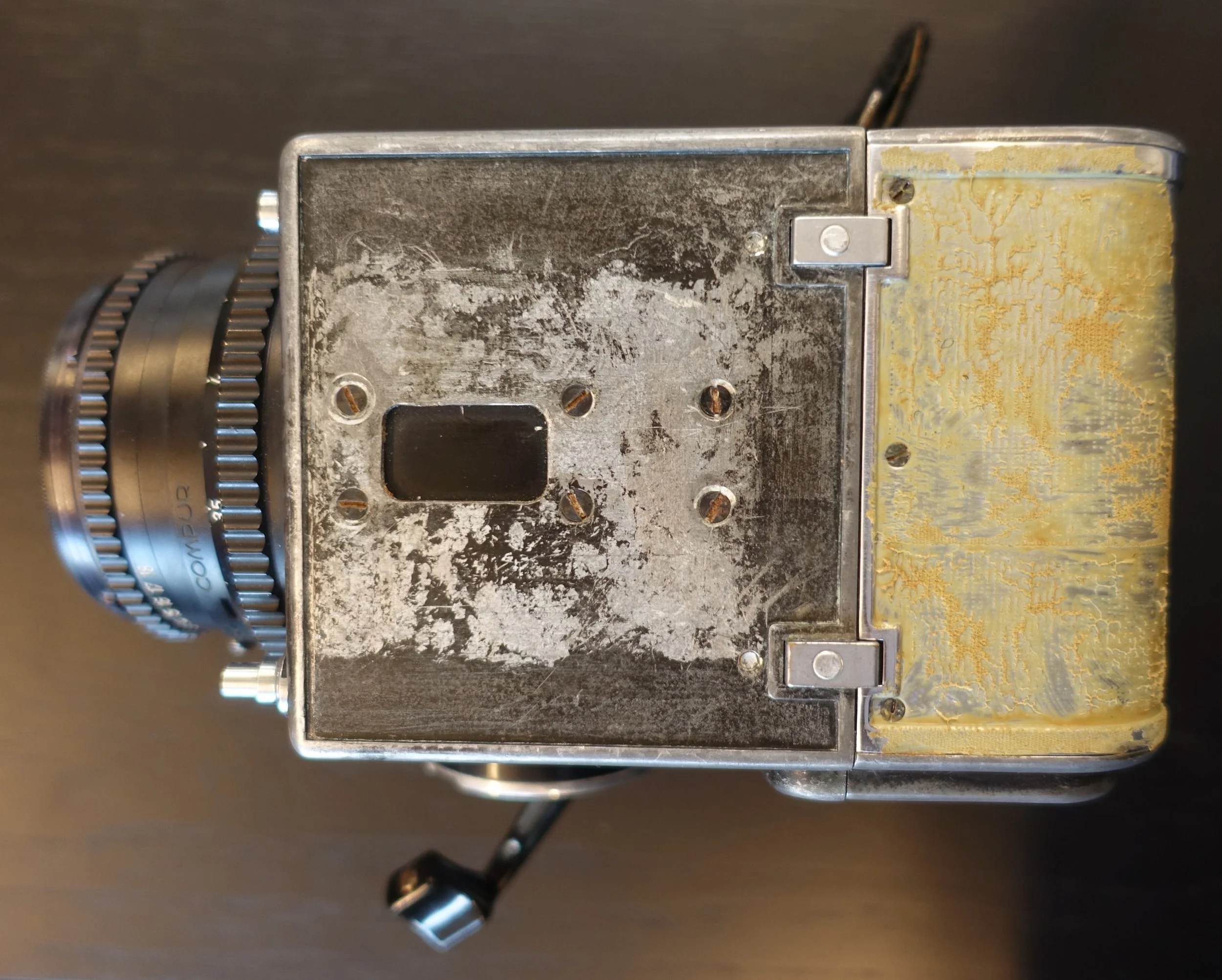

The breakthrough came by examining the top the camera, where you can see witness marks from the chemical blackening process. Acid was painted onto the aluminum with a brush, causing it to form a black oxide layer that made the camera less reflective in the spacecraft window. The resulting patina had tell-tale brush strokes that acted like a fingerprint of it’s creation. Looking closer, you can also observe the unique placement and rotation of the 1-72 brass slotted screws on that same cover. They’re noticeably sloppier than the auction camera. One screw is awkwardly out of place, jutting to the side and ruining the symmetry of the top cover. It almost looks rushed, which would make sense for a last-minute hand-modified addition to a flight. All of these details perfectly match Steve’s camera.

MA-8 Preflight Photo (LOC-62-7465)

MA-8 comparison with Steve’s camera.

We can now say with a very high degree of confidence that Steve Jurvetson has the original MA-8 camera body - the First Hasselblad in Space. Thank you, Jerome, for the seemingly small, but key piece of evidence.

But what about the one that sold at auction? Was that the MA-9 body?

MA-9 Preflight Photo (LOC-63C-1339)

The second MA-9 preflight photo was harder to find. After weeks of searching, it finally turned up smack in the middle in an old auction listing photo, surrounded by eight other prints included in the lot, and not in the highest resolution. Still, it was something I could work with.

Titled "Spacecraft 20 Gear Packed for Flight,” it was dated May 8,1963, a week before liftoff. It’s not known if this is the publication date of the photo, or the date the photo was taken, but one can assume it was close to launch. The image shows a Hasselblad 500C among other equipment that are unique to the mission, including a lesser known 35mm Robot Recorder. Again, it’s the chemical patterns that can be matched, this time to the camera that sold at auction — now clearly the second Hasselblad in space.

MA-9 Preflight Photo (LOC-63C-1339)

MA-9 preflight photo with the auction camera showing matching scratches & screw placement.

Swapped lenses, and the MA-9 Camera hidden in plain sight.

What about the lenses? The interchangeability of the Hasselblad may have had its virtues in space, but it makes it rather difficult to trace provenance when most parts can be so easily mixed and matched. This is likely where the auction house was steered off course — at some point the lenses were switched.

How can you tell? Looking closer at the auction lens, you can see a unique defect in the depth of field indicator; a small scratch or ripple in the paint with the underlying aluminum peeking through. This same defect can be seen on the lens in the MA-8 preflight photo. The serial number of the auction lens also seems to match the serial of the one in Schirra’s hands during his preflight checkout of the equipment. The auction lens really is the MA-8 lens, and the first Carl Zeiss in space.

What about the lens on Steve’s camera? Well, remember that second, unmodified Hasselblad in front of Schirra? Yep, the serials match. Incredibly, the cold shoe on the side of the camera also matches the auction camera, so in that photo we likely have a glimpse of the MA-9 camera before it was modified.

Now, when or why the lenses were swapped is still an open question. Maybe the MA-8 lens was already flight proven, or sharper, and NASA chose to re-fly that one… or, maybe, while documenting the modifications of the camera for posterity, the two were accidentally put onto the wrong bodies. This is all conjecture until we can find a higher resolution image of the MA-9 preflight photo, but hey, at least the auction got it half right.

Comparing Steve’s lens with the camera in front of Schirra before his flight. Both serial numbers match.

Auction camera cold shoe matches the same, unmodified camera seen shortly Schirra’s flight. It would go on to be modified for MA-9

Two stories, two missions, two camera bodies, two lenses, with testimony from two astronauts. Let’s set the record straight.

Here’s what we now know with high probability:

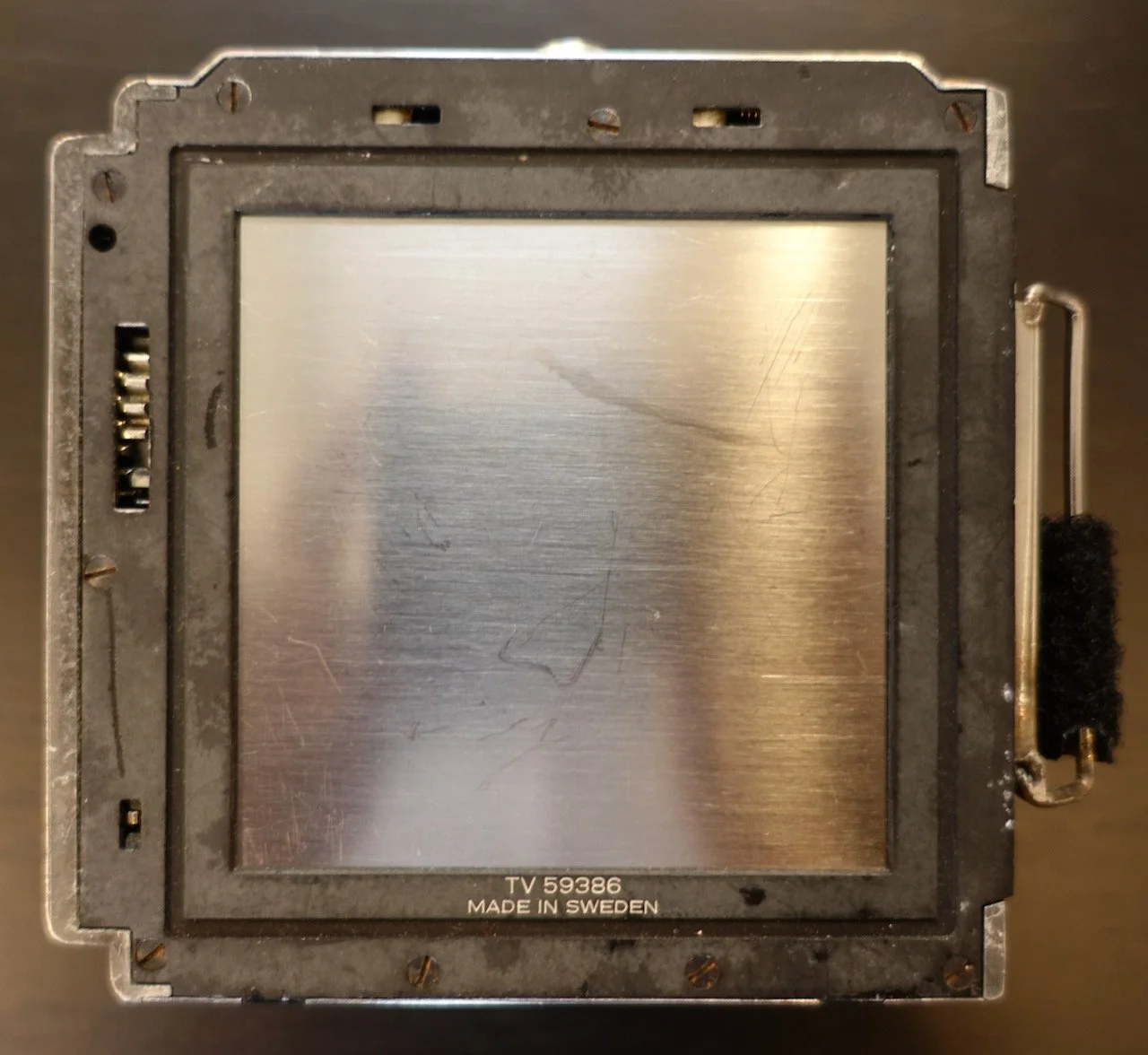

On October 3rd, 1962, Wally Schirra used Hasselblad TV 45011 with 2 film magazines, one serial number TV 59386, and an 80mm Carl Ziess lens Nr 282380 on Mercury-Atlas 8. The body is owned by Steve Jurvetson, and the lens by the auction winner.

On May 15th, 1963, Gordon Cooper used Hasselblad TV 45279 with 3 film magazines, including serial number TV 59228, and an 80mm Carl Zeiss lens Nr 2823801 or Nr 2575850, on Mercury-Atlas 9. The body is with the auction winner, and one of the lenses, possibly unflown, is with Steve Jurvetson.

At some point, the lenses were swapped, either before or after MA-9, which resulted in the MA-8 lens ending up on the MA-9 body.

Final thoughts & acknowledgments

RR Auction is a super reputable auction house from which I frequently purchase amazing items. They had really good documentation, even the word of an astronaut, but were misled by an ambiguous caption under a photo. I will be participating in their upcoming October auction, nonetheless.

I hope the private collector who won the auction camera knows the truth, having items from the last two Mercury missions: the first Carl Zeiss lens in space, and the flown MA-9 Camera.

Identifying flown equipment can be vastly complicated from such a poorly documented era for NASA. It's hard to find super dependable information, which is the inspiration for writing this article. My hope is to simply correct the record.

Thank you to:

Steve Jurvetson for the access to your camera & collection, and your patience while researching and writing this article.

Andy Saunders for the fantastically remastered image of Schirra using his camera in space. It’s one of many he’s diligently restored in his latest book, now available on Amazon.

Jerome Bascom-Pipp for the high-res preflight photo that helped crack the case.

Mike Smithwick, author of Distant Suns on iOS, for additional photos of the MA-8 camera

CollectSpace.com for the wealth of information & capturing some the images featured above.